Centering Communities: A Human Security Approach to Peacebuilding in Sudan

Anab Mohamed

8/1/20259 min read

Executive Summary

Sudan’s ongoing crisis highlights a critical gap in global peacebuilding: the exclusion of grassroots actors from processes that directly impact their future. While international stakeholders continue to champion civilian governance and democratic transition in rhetoric, current peace efforts often replicate elite-driven, top-down frameworks that lack legitimacy and sustainability. This policy brief calls for a fundamental shift in how peace is conceptualized and practiced, centering local actors as co-creators of peace and linking localized peacebuilding to human security. Localized peacebuilding is not only more legitimate, it is more effective, more contextually relevant, and essential for breaking the cycle of protracted conflict.

Background and Context

Since gaining independence in 1956, Sudan has endured over six decades of armed conflicts, military coups, and turbulent political transitions. These conflicts have been fueled by deep-rooted grievances related to marginalization, unequal distribution of power and resources, and identity-based exclusion.

Numerous peace initiatives, such as the 2005 Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA), the 2011 Doha Document for Peace in Darfur, and the 2019 Constitutional Declaration, have sought to address Sudan’s persistent instability and violence. However, these initiatives largely included armed and political elites while excluding people with lived experience of war: civil society actors, youth, women, grassroots groups, and resistance committees. Even after the fall of Sudan’s three-decade authoritarian regime in 2019, transitional processes continued to follow an elite-driven and externally brokered pattern that sidelined the very women, youth, and community actors who led the revolution which ended the 30-year dictatorship of Omar al-Bashir.

Sudan’s current war between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which erupted in April 2023, has followed a similar pattern. International mediators, including the United States, Saudi Arabia, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD), the African Union, and the UN, have led several failed efforts to negotiate an end to the fighting. Through most formal and informal peace initiatives since the war began (e.g Jeddah talks, IGAD-mediated efforts, UN-mediated initiatives, US-led efforts, and international conferences), the SAF and RSF were the primary participants, with international mediators facilitating talks. Civilian stakeholders, including grassroots actors, neighborhood and resistance committees, women’s groups, and displaced communities, were consistently absent and excluded from formal peace negotiations, eroding the legitimacy of these negotiations and reinforcing the notion that political legitimacy is earned through either regional and global projections of power or force, not community leadership.

Evidence from peacebuilding research underscores the importance of localized peacebuilding, demonstrating that locally led efforts are often more sustainable, contextually relevant, and effective in addressing the root causes of conflict. The continued pattern of marginalization of local actors in regionally and globally brokered peace processes has resulted in fragile and subsequently failed peace efforts and revealed a fundamental disconnect in how human security is conceptualized and operationalized. There can be no true human security if the very people whose security is at stake are not central to its design. Understanding Sudan’s peacebuilding trajectory is essential not only for supporting its current path toward peace but also for informing global efforts in conflict resolution and humanitarian action.

Why Local Peacebuilding Matters

Many communities and cultures across Africa have traditional, community-based conflict resolution mechanisms that have existed for generations. In Sudan, one such traditional conflict resolution mechanism is known as Judiya. In Sudan, especially in rural and pastoralist communities, Judiya has been embedded in local customs and has historically played a crucial role in mediating disputes, maintaining social cohesion, and fostering peace. Judiya is typically led and facilitated by Ajaweed, who are highly respected elders or dignitaries who facilitate the Judiya process. This model is a vibrant example of indigenous peace mechanisms that remain largely absent from formal negotiation tables. Sudan’s communally sponsored Judiya and Ajaweed serve as a potential example of what is possible. During the ongoing war, there have been instances where local tribal leaders, elders, or community mediators have succeeded in brokering temporary ceasefires or localized truces between the Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) and the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). For example, from April 17-18, 2023, the Elders and Mediation Committee (EMC) formed by local dignitaries reached a ceasefire agreement with both SAF and RSF commanders. They secured safe burials, medical evacuations, and monitored troop movements, with demarcation lines upheld by police forces. Similar community-led ceasefires were reported in West Kordofan and East and West Darfur.

One-day ceasefires are far from ending a full-scale war, but they are significant because they demonstrated the weight and legitimacy the negotiated agreements received due to the role of local elders and tribal leaders who possess deep-rooted community respect, and how they enabled humanitarian corridors, medical access, burials, and reduced immediate violence. While not widely publicized or sustained at the national or global levels, these localized traditional mechanisms have great potential in fostering sustainable, inclusive, and contextually grounded peace. The engagement of local leadership in peacebuilding is strategically relevant and, when sufficiently fortified and invested in, represents a strategically scalable mechanism that can be replicated and subsequently harnessed in Sudan and regionally.

The Emergency Response Rooms (ERRs)—networks of grassroots committees formed during times of crisis—have demonstrated extraordinary capacity to coordinate civilian protection, document and respond to gender-based violence survivor needs, distribute aid, and mobilize collective action. Their model exemplifies what effective, community-rooted governance can look like. ERRs have gained growing recognition from international donors for their demonstrated effectiveness in delivering humanitarian assistance amidst conflict. As a result, donor funding has increasingly been directed toward these community-led mechanisms. While this trend underscores a strategic understanding that investing in local leadership structures now is essential to laying the foundation for a sustainable and peaceful future in Sudan, community leaders still remain sidelined from internationally-led peace processes.

Sudanese women have also historically played crucial roles in conflict resolution, social cohesion, and mobilization, both during civil wars and transitional periods. They continue to play essential roles in community-based peacebuilding, such as mediators in Judiya (traditional mediation) processes, leading neighborhood committees and humanitarian responses during war. Several well-documented peace initiatives were led or shaped by Sudanese women. For example, the Peace for Sudan Platform, a coalition of over 49 women-led peace and humanitarian initiatives across Sudan, organized a high-level virtual solidarity mission and a regional conference in Kampala in October 2023, representing over 400 women from 14 Sudanese states, refugee and diaspora communities. Women leaders in ERRs have also been central to local coordination, support, and protection efforts.

The US has supported women’s participation in Sudan’s peace process through the Women, Peace, and Security Act (2017), with the Office of Global Women’s Issues (GWI) facilitating the presence of 12-15 Sudanese women civil society representatives at the Aligned for Advancing Lifesaving and Peace in Sudan (ALPS) talks in Geneva. However, their participation and presence were largely symbolic; they did not gain formal negotiating roles in the talks themselves. Since the closure of the GWI under the Trump administration, there is now a critical gap in US government advocacy for Sudanese women’s inclusion in peace processes.

Challenges to Localized Peacebuilding

Sudan’s political complexity holds both promise and challenge. The same dynamics that make it fertile ground for localized peacebuilding, also hold the roots of obstacles towards its practice and implementation. The deep-rooted history of grievances, armed strife, political instability, and remnants of authoritarian legacies all contribute to the current pattern of exclusionary practices that dominate and shape peacebuilding discourse, regionally and globally.

While localization gains momentum in international discourse, many external actors continue to reproduce exclusionary patterns. Elite-driven, externally brokered peace processes are still shaped by expediency, oftentimes prioritizing armed and elite actors believed to hold power and leverage, while sidelining the very communities who have sustained the social fabric throughout conflict. These dynamics reflect deeper global power asymmetries that are rooted in colonial legacies–power structures, knowledge hierarchies, and institutional logics inherited from colonial rule–which continues to undervalue local wisdom and lived experiences of those who travailed in wars.

Internally, Sudan’s fractured civilian landscape, shaped by decades of repression, division, mistrust, and marginalization, makes unified organizing a steep uphill battle. Armed actors exploit these divisions to further divisive rhetoric and volatile discourse, and community peacebuilders often operate under threat. In some cases, local actors are forced to align with elites or either of the armed groups to survive, even when it compromises their legitimacy.

The centralized structure of the Sudanese state, built on authoritarian legacies, resists the decentralization of power that any localization efforts demand. Traditional conflict resolution mechanisms, and subsequently social cohesion, have been eroded by war, displacement, and urbanization, and in some cases deliberately undermined by past conflicts. Ultimately, both domestic and international actors often lack the political will to disrupt existing hierarchies, as doing so would require meaningful redistribution of power and resources.

Deciding not just who should be included in political and peace processes but also how they participate is one of the biggest challenges to localized peacebuilding in Sudan. While inclusivity is important, it becomes complicated when some of the actors seeking inclusion are the same ones who contributed to Sudan’s collapse—such as members of the former National Congress Party (NCP) regime, or other parties that are aligned with any of the armed actors. Groups like the NCP have a long history of violence, corruption, and oppression, and many Sudanese no longer see them as legitimate. If any participation of these groups is to be considered, it should prioritize civilian-led, community-rooted actors over co-opted elites; establish minimum thresholds of accountability and transparency before granting political space to formerly harmful actors; designed with transitional processes that elevate the leadership of war-affected communities, women, youth, and resistance committees; and be rooted in community trust, and community-defined legitimacy.

Tokenistic inclusivity in peacemaking by the superficial or symbolic inclusion of local actors–such as women, youth, civil society, or traditional mediators–without granting them meaningful power or decision-making roles, has been a recurring issue in Sudan’s political transitions and peace processes. This façade allows international mediators and national elites to claim representational legitimacy without making structural changes that enable meaningful participation. In doing so, it blurs accountability for genuine inclusion and delays the transformation of peace processes into ones that are truly locally owned. Rather than advancing peace, this performative inclusion undermines trust, reinforces marginalization, and reproduces the very exclusionary dynamics that have historically fueled Sudan’s conflicts.

Localized peacebuilding, while not a substitute for blocking external enablers of war, is essential for building the foundations of legitimacy, trust, and pressure from the grassroots. A people-centered approach to peace requires both disrupting the incentives to fight and investing in community-rooted mechanisms that shift the center of gravity away from armed actors toward those living its impacts.

Without a real shift in political will, both from domestic elites and international actors, calls for localized peacebuilding risk becoming empty rhetoric rather than a pathway towards transformative peacebuilding.

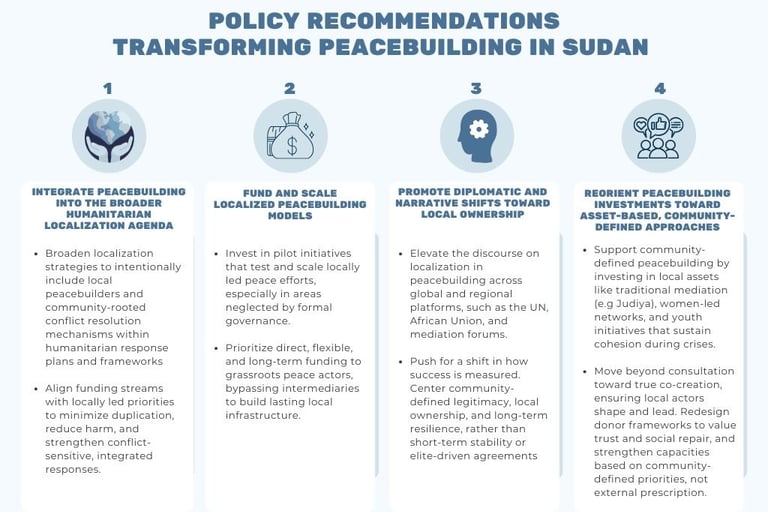

Policy Recommendations

Integrate Peacebuilding into the Broader Humanitarian Localization Agenda

Broaden localization strategies to intentionally include local peacebuilders and community-rooted conflict resolution mechanisms such as Judiya traditional mediators, Sudanese women’s groups (e.g Peace for Sudan Platform, Women Against War, Mothers of Sudan, the Red Sea Organizations’ Initiative and Women’s Situation Rooms) and the Elders and Mediation Committees (EMCs) within humanitarian response plans and frameworks. Align funding streams with locally led priorities to minimize duplication, reduce harm, and strengthen conflict-sensitive, integrated responses.

Fund and Scale Localized Peacebuilding Models

Invest in pilot initiatives led by grassroots actors that demonstrate community mediation, local ceasefires, and social healing, whether in Darfur, Kordofan, or recently impacted urban centers like Khartoum and Wad Madani. Prioritize direct, flexible, and long-term funding for these peacebuilding actors, especially in areas where state governance has collapsed and local social structures, such as Judiya councils, faith-based spiritual networks, ERRs, neighborhood committees, and mutual aid networks remain the primary source of order and protection. Bypass top-down intermediaries to build infrastructure for durable, community-rooted peace. These structures are highly localized, responsive, and rooted in social legitimacy. They are often the first to respond to crises, and when supported properly, they can serve as the backbone of locally led peacebuilding and humanitarian response.

Promote Diplomatic and Narrative Shifts Toward Local Ownership

Elevate the discourse on localization in peacebuilding across global and regional platforms, such as the UN, African Union, and mediation forums, and push for a shift in how success is measured. Amplify narratives of Sudanese civilian leadership in peacebuilding, centering community-defined legitimacy, local ownership, and long-term resilience, rather than short-term stability or elite-driven agreements.

Reorient Peacebuilding Investments Toward Asset-Based, Community-Defined Approaches

Support community-defined peacebuilding by investing in Sudan’s endogenous conflict resolution traditions like traditional mediation (e.g Judiya), women-led networks, and youth initiatives that sustain cohesion during crises. Move beyond consultation toward true co-creation, ensuring local actors shape and lead. Redesign donor frameworks to value trust and social repair, and strengthen capacities based on community-defined priorities grounded in Sudanese cultural and social realities, not externally prescribed.

Conclusion: Rethinking and Reshaping Peacebuilding Dialogue

At its core, human security is about safeguarding the dignity, safety, and agency of individuals and communities. In Sudan, where protracted conflict continues to destroy lives and futures, the failure to center local actors in peace processes is a failure of centering dignity and agency, reflecting a profound misreading of what human security truly demands.

Community-centered peacebuilding in Sudan can foster legitimacy, address root causes, and sustain peace where formal institutions have failed by elevating trusted local actors like resistance committees, traditional mediators, and women-led networks. Globally, it offers a scalable, alternative to elite-driven models, challenging extractive systems and redefining peace as a bottom-up process rooted in community agency.

Anab Mohamed is a Sudanese-American policy consultant and founder of Pathways Consulting LLC, an emerging boutique agency focused on advancing locally-led, systems-informed solutions in humanitarian response and peacebuilding. Her work integrates lived experience with policy analysis to reframe aid and security through the lens of community agency and resilience.

Acknowledgements

This policy brief is a collaborative effort made possible through the support of the Human Security Project. The author is especially grateful to Mike Brand for his partnership in co-developing the core ideas and arguments of the brief, and to Rosie Berman for her generous and thoughtful editorial guidance throughout the writing process.

Human Security Project

Delivering bold, actionable interventions to prevent violence, protect people, and build human security.

Connect

Engage

© 2025. All rights reserved.